Undertale: A Tale Composed by Both the Developers and the Gamers

Heidegger's conception of technology centers on its capacity for revealing, suggesting that the essence of technology does not merely reside in skills and knowledge, but rather in the process of poiesis - the artistic process of bringing something hidden into view (Heidegger 12). As such, technology, rather than being solely a result of human activity, is a dynamic product that is deeply intertwined with the process of human development, mirroring the changing society and serving as a space for learning about culture. In this contemporary landscape dominated by various new media, video games have emerged as a distinct form of media, offering interactive and participatory narratives that allow for a dialogue between the player and the game world. The present paper, therefore, aims to analyze the game Undertale, demonstrating how it serves as a vehicle for revealing the idea of culture jamming and emphasizing the crucial role of players' active agency. It will also explore how the game embraces the idea of cosmopolitanism, and how the game ultimately illuminates humans' desire for the imagined "homeland."

Undertale (Fox 2015) is a unique roleplaying game in which players take on the role of a child who falls into a world of monsters and must make decisions about how to interact with them. The game is heavily influenced by the Japanese Roleplaying Game (J-RPG) genre, which typically features a linear narrative where characters increase in strength by gaining experience points (EXP) through fighting monsters, including challenging boss monsters (Veale 455). However, Undertale breaks away from the norm by giving players the option to engage in combat or avoid it. During battles, players can choose between four options: FIGHT, ACT, ITEM, and MERCY (see Fig.1). FIGHT involves a mini-game based on timing and accuracy, ACT enables special actions depending on the enemy, ITEM allows players to change equipment and use healing items, and MERCY provides the option to flee or offer the enemy a chance to escape. After selecting an option, the menus disappear, and players control a red heart that must avoid waves of enemy attacks (see Fig.2). The types of attack and their difficulty vary depending on the enemy's current state of mind.

Undertale (Fox 2015) is a unique roleplaying game in which players take on the role of a child who falls into a world of monsters and must make decisions about how to interact with them. The game is heavily influenced by the Japanese Roleplaying Game (J-RPG) genre, which typically features a linear narrative where characters increase in strength by gaining experience points (EXP) through fighting monsters, including challenging boss monsters (Veale 455). However, Undertale breaks away from the norm by giving players the option to engage in combat or avoid it. During battles, players can choose between four options: FIGHT, ACT, ITEM, and MERCY (see Fig.1). FIGHT involves a mini-game based on timing and accuracy, ACT enables special actions depending on the enemy, ITEM allows players to change equipment and use healing items, and MERCY provides the option to flee or offer the enemy a chance to escape. After selecting an option, the menus disappear, and players control a red heart that must avoid waves of enemy attacks (see Fig.2). The types of attack and their difficulty vary depending on the enemy's current state of mind.

Fig.1 Undertale offers players the options of "ACT" and "MERCY" during battles; ACT allows for a range of actions to be performed depending on the enemies, their current mind states and players' previous choices.

Fig. 2 The player's character is represented by a red heart and must navigate through a series of enemy attacks, which vary in types and difficulty levels based on enemies' current mind state and players' previous choices.

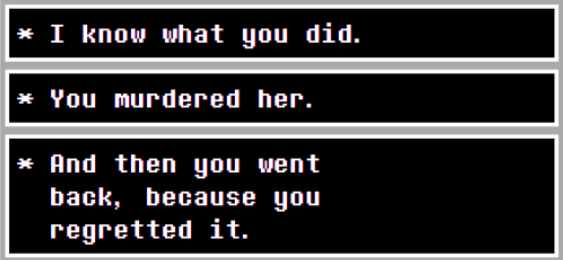

Undertale subverts traditional RPG gameplay mechanics by emphasizing that the player is the one making the decisions rather than the character they control, and encourages the players to reject violence and encourages nonviolent conflict resolution. This mechanics can be understood as a form of "culture jamming," which involves appropriating new media technologies and information systems to disrupt established norms and values (Wilson 324). To illustrate, the game deliberately breaks the fourth wall, blurring the line between the avatar and players and employing a unique save-file system: a system that remembers the player's every choice and action throughout the game, even if the player loads a previous save file to overwrite those actions (see Fig. 3). Indicated through conversations with characters, Undertale's memory system is notable. When the protagonist Flowey confronts a player who has chosen to kill Toriel - the first "enemy" and friend encountered in the game - and attempts to reload the file to "un-kill", Flowey makes a revealing statement: "I hope you like your choice. After all, it's not as if you can go back and change fate ... Then you decided that just wasn't interesting enough for you. So you murdered her just to see what would happen. You killed her out of boredom" (Fox 2015). This dialogue illustrates that Undertale's memory system is comprehensive, and that the consequences of killing a character cannot be erased. The game further challenges the typical RPG concept of experience points (EXP) and level progression, instead redefining EXP and LOVE as "EXecution Points: a way of quantifying the pain you have inflicted on others" and "Level Of ViolencE: a way of measuring someone's capacity to hurt," and reminding players that "You will be judged for every action. You will be judged for every EXP you earned" (Fox 2015). Through these designs, Undertale constitutes a poignant critique of the "kill or be killed" mindset that pervades not only video games, but also broader gaming culture and, by extension, the real world.

Fig. 3 Undertale remembers every action taken by the player, which is conveyed through conversations with characters such as the antagonist, Flowey. In the example shown above, Flowey reminds the player that they had previously murdered a mother-like monster and then reloaded the save file.

In addition to its critiques of violence structure in mainstream video games, Undertale also challenges the concept of completionism, which is a popular feature in most games. Completionism is the desire to explore every aspect of a game to see different reactions and endings, even if it means replaying it multiple times (Brewis). Undertale constantly prompts players to consider the moral implications of their actions within the game world to counter the idea of completionism. For example, despite the game offers different endings based on the route chosen and the number of playthroughs completed, it again reminds players that their actions have consequences at the end of the journey: replaying the game can reverse the progress made in the previous playthroughs and rip the happy endings that have been achieved. Undertale's emphasis on morality and players' responsibility is especially evident in the Genocide Route, where players kill every monster in the game. The genocide route penalizes the player with monotony and tedium, as most dialogues disappear and the player's sole objective becomes to indiscriminately kill every character they encounter. In this route, a message appears at a certain point during the battle that says "but nobody came," signaling the player's destruction of the game's world and its inhabitants: they are either dead or have fled in fear (see Fig. 4). Undertale undermines the typical power fantasies present in RPGs by adding a moral dimension, creating a simulation of responsibility, guilt, and moral conflict in players (Travers). This serves to challenge and resist the prevailing consumerist culture of completionism.

Fig. 4 "But nobody came" (Fox 2015).

Therefore, Undertale's aim extends beyond criticizing traditional RPGs' framework and delves into critiquing the current trend in a broader fan culture: obsessing with cataloging and quantifying every aspect of a game, seeking to uncover every hidden detail. Undertale further illustrates that curiosity should be grounded in compassion towards others, and the desire to understand them better, rather than solely driven by the completionist urge. The enjoyment of playing a game, or engaging in any activity, should come from the experience itself, not just from accumulating achievements. This notion aligns with Heidegger's concept of technology, which he refers to as "enframing," a term that signifies how modern technology has transformed the world into a mere standing reserve, where everything is viewed as a potential resource for human use (Heidegger 48). As demonstrated in Undertale's EXP judgment: "The more you kill, the easier it becomes to distance yourself. The more you distance yourself, the less you will hurt. The more easily you can bring yourself to hurt others" (Fox 2015). This idea is also echoed in the documentary Coded Bias: "What it means to be human is to be vulnerable. Being vulnerable, there is more of a capacity for empathy, there is more of a capacity for compassion" (Kantayya). In this case, Undertale serves as a warning against treating everything as a mere resource to collect, as doing so can have disastrous consequences: there is nothing left, no monsters, no underworld, and definitely, no more tales.

Undertale's critique of completionism can be applied to real life, where the incessant desire to consume and explore every facet of the world can lead to consumerism and exploitation. A prime example of this phenomenon can be seen in the documentary "Generation Like," where individuals seek validation through social media likes, often treating themselves and others as mere resources to increase their online presence. This objectification of oneself and others can result in a loss of empathy and compassion, similar to how Undertale's continual mindless killing can desensitize and distance players from the game's world and characters.

As shown, Undertale also emphasizes the active role that players take in shaping the narrative through their different choices. Being a self-reflexive game, Undertale requires players to make careful decisions instead of mindlessly attacking, forcing players to be aware of their active agency in shaping the game's story. The game satirizes the mindset of players who engage in questionable actions in mainstream games simply because they can, as character San's taunt "you're not doing this because you're evil. You're doing this because you can, and because you can you feel you have to" implies (Fox 2015). Undertale's message regarding the relationship between power and responsibility can be extended to different facets of human life, such as the utilization of technology, natural resources, and interactions with vulnerable individuals. Undertale prompts players to reflect on the relationship between power and responsibility, reminding them that just because they have the ability to do something, it does not mean they have to do it. Also, instead of giving credit solely to the end result, the game recognizes and values the players' struggles and the decisions they make along the way. As the game puts it, "You never gained any LOVE. 'Course, that doesn't mean you're completely innocent or naive. Just that you kept a certain tenderness in your heart. No matter the struggles or hardships you faced... You strived to do the right thing" (Fox, 2015). In a world full of temptations, kindness and empathy may not come naturally to people, but rather stem from the effort and determination people put into doing the right thing, even in challenging circumstances.

Undertale's focus on player agency and culture jamming mechanics ties into its broader message of promoting acceptance, empathy and cosmopolitanism. The game's monsters possess distinct personalities and hobbies, yet they tolerate and appreciate one another's interests. It highlights how easy it is for individuals to dismiss the passions of those who are different from them. Cosmopolitanism, on the other hand, emphasizes the importance of tolerance and respect for "legitimate difference," and encourages people to seek commonality across differences (Stornaiuolo et al. 264). It is important to common ground in small moments; luckily, despite changes in time and space, the emotions of people, and even monsters, stay the same. Undertale's portrayal of cosmopolitanism underscores the idea that accepting and celebrating differences can lead to greater understanding, empathy, and ultimately, a more harmonious society.

Undertale's ability to foster empathy and create a sense of community has contributed to its broad appeal, particularly in a time when many long for a sense of continuity and connection in a rapidly changing world. Technology that once promised to bridge modern displacement and distance and provide the miracle prosthesis for nostalgic aches has itself outpaced the nostalgic longing it sought to heal. Instead, technology and nostalgia have become co-dependent, which led to a global epidemic of nostalgia, a yearning for a community with a shared memory and a longing for continuity in a fragmented world (Boym 10). Since media consumption is a purposeful activity (Katz 510), Undertale satisfies the modern desire for belonging, both within the game's underworld with monsters and in real-life fan communities.

In addition, as Svetlana Boym observes, "nostalgia is not always retrospective; it can be prospective as well. The fantasies of the past, determined by the needs of the present, have a direct impact on the realities of the future" (Boym 8). This sense of belonging, this sense of nostalgia for an imaginary land in video game, in fact mirrors one's idealized self and the desired relationship between the individual's personal story and the larger narrative of social identity. Further, Undertale offers more than just an escape from reality. It presents a fantastical world that serves as a parallel simulated space for players to explore their own identities and learn how to build relationships with others in real life.

While the popularity of Undertale may suggest a desire for a more empathetic society, it is important to avoid the trap of utopian technological determinism and acknowledge that playing video games obviously are not the way to achieve this goal. Undertale is aware of its status as a game and uses its self-reflexivity, breaking of the fourth wall, and anti-competition feature to suggest that it is just that - a game. The game's meta aspect emphasizes that the themes presented are meant to apply to real life, and players are essentially playing as themselves in the game world (“Undertale | Philosophy of Megaten Wiki | Fandom”). Ultimately, Undertale pushes players to reflect on their experiences and relationships in real life and encourages players to make "better choices than the ones that they might feel pulled along to do" in reality (“Undertale | Philosophy of Megaten Wiki | Fandom”).

In conclusion, Undertale serves as a unique video game that functions as a culture jammer and highlights players' agency. The game's focus on cosmopolitanism and the concept of a desired "homeland" reflects humanity's inherent need for empathy and comprehension, even in virtual spaces. In the world of gaming, players create online avatars and participate in virtual communities, which may undermine the notion of a real and unitary self. Yet, players in real life are nevertheless bound by the desires, pain, and mortality of their physical selves (Turkle 267). The problems of the real world persist in virtual spaces: Who am I? Who do I want to be? What is the relationship between me and the world? It's simple to become lost in the shattered network and trapped in the illusory joy that comes with ceaseless data and traffic; everything is making it easier for people to succumb to different temptations. However, as Undertale intends, as we all hope, and hopefully we all will - "despite everything, it's still you" (Fox 2015) (see Fig. 5).